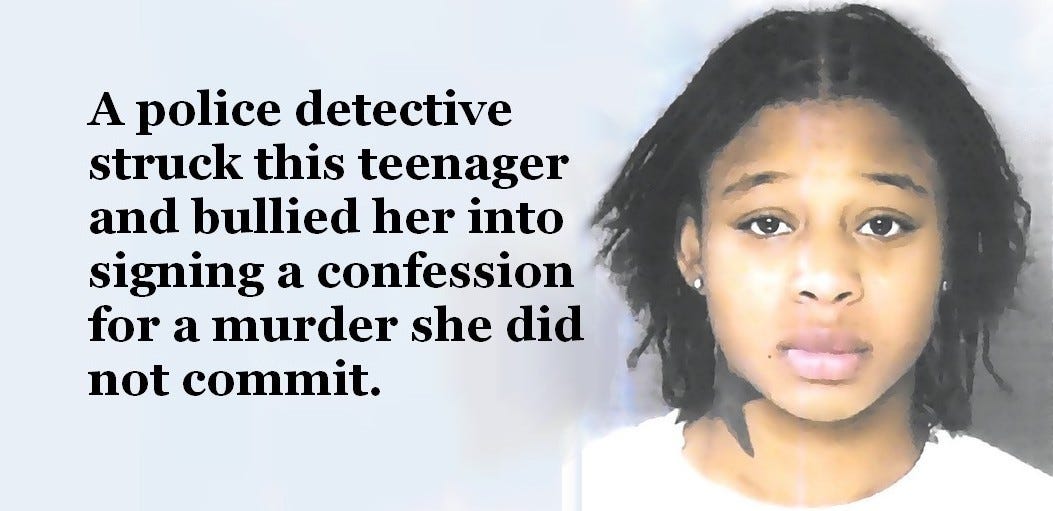

Does your prosecuting attorney's office have a conviction integrity unit? Less than 5 percent do, But they can be a potent force for justice. Such a unit fought for the freedom of India Spellman, above, arrested at age 17 for a murder she did not commit.

The Philadelphia jury that convicted her saw what appeared to be an ironclad case. The prosecution introduced Spellman's own confession into evidence, as well as the confession of her supposed accomplice. The prosecution also presented an eyewitness who had seen a man and woman running from the crime scene and identified Spellman as the woman.

But in fact, the teenager was at home, talking on the phone, when the crime occurred. Her wrongful conviction resulted from a near perfect storm of injustice.

For decades, the Philadelphia police homicide detectives got away with, if not murder, at least assault and sometimes torture, to extract confessions from suspects being interrogated. A 1977 investigation by the Philadelphia Inquirer revealed that some detectives used blackjacks and brass knuckles, as well as other techniques which did not leave a severe bruise. Those techniques included, the newspaper reported, "placing a telephone book on a suspect's head and hammering it with a heavy object; beating his feet and ankles; twisting or kicking his testicles; and pummeling his back, ribs and kidneys."

The rhetoric of Philadelphia's mayor at the time, ex-cop Frank Rizzo, did nothing to discourage this brutality. Rizzo had promised voters "I'm going to make Attila the Hun look like a faggot." The lawless attitude, if not the crude language, continued after Rizzo's term ended.

Incidents of brutality by Philadelphia homicide detectives kept resulting in lawsuits costing the city millions of dollars, Yet the police department didn't change. Additionally, judges kept believing the detectives’ testimony when they denied the brutality and swore the confessions were voluntary.

No one in local government held the police accountable until Larry Krasner took office as Philadelphia district attorney in January 2018. His office prosecuted homicide detective Philip Nordo. In 2022, Nordo was convicted of rape and other crimes.

Krasner’s office secured indictments against other homicide detectives, including James Pitts, who brutally interrogated India Spellman and then lied about it when he testified. Pitts was indicted for perjury in another case, unrelated to Spellman’s. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that Pitts had been the subject of at least 11 citizen complaints.

Spellman’s encounter with Pitts took place in 2010, after a robbery and a murder by a young man and woman. Detectives coerced a confession from a 14-year-old boy, who said falsely said that India Spellman was with him and pulled the trigger. Police took Spellman to an interrogation room at police headquarters.

Her father insisted to the detectives that he wanted to be present and wanted his daughter to have a lawyer present but they wouldn’’t allow it. When he tried to reach his wife, they confiscated his phone. When his wife arrived at the police headquarters, the detectives lied, saying that India already had confessed. In fact, the interrogation had not yet begun. Then, the cops escorted her parents out of the building.

In the interrogation room, Detective James Pitts yelled at the teenager and hit her. He handed her a written confession but, although India had a reading disability, refused to read it to her. He told her she could go home if she signed it. She did, but rather than let her leave, Pitts booked her on a murder charge.

At her trial, Pitts denied hitting her and claimed that neither she nor her father had requested a lawyer. The judge believe the lies and allowed the confession into evidence.

The witness who saw two people run from the murder scene identified Spellman. Earlier, this witness had told police that she had not seen the woman's face, but that fact was not disclosed to the defense.

Additionally, Spellman's own lawyer did a terrible job. He could have called her grandfather, a former police officer, to testify that she was at home at the time the murder occurred. The lawyer did not. He also could have asked Spellman's father questions to establish this alibi but did not.

Spellman’s attorney also had cellphone data showing that the teenager was talking on the phone, at a location not near the murder scene, when the crime occurred. However, he did not offer these records into evidence.

The jury found Spellman guilty of murder, robbery and related offenses. The court sentenced Spellman to serve 30 years to life in prison. Spellman lost on appeal and likely would still be in prison except for the efforts of District Attorney Krasner, and his conviction integrity unit.

When Krasner took office in 2018, Spellman was in prison. Although Krasner’s predecessor had established a conviction integrity unit, it did little until Krasner increased its funding and hired an experienced conviction review attorney to head it. In less than 5 years, the invigorated conviction integrity unit exonerated 32 innocent people.

The unit found a note in Spellman's file which indicated that, during the investigation, the witness who identified Spellman in court had told police that she had not seen the suspects' faces. The prosecutors turned the note over to Spellman's new lawyer and continued with their investigation.

While seeking India Spellman's exoneration, the conviction integrity unit filed numerous pleadings. One included a report by an expert on eyewitness identification. Another pleading presented a forensic analysis by a cellphone expert, showing that Spellman was not near the murder site when the crime occurred.

Additionally, one of the pleadings described in detail Detective Pitts’ indictment for misconduct in another case. Still, the judge wasn't easy to convince.

Finally, on February 9, 2023, the court vacated Spellman's convictions. She was free after spending 12 years, 5 months and 20 days behind bars.

Some of Krasner's policies - declining to prosecute individuals for possession of marijuana and instructing his prosecutors not to seek cash bail for certain relatively minor offenses - have drawn vigorous criticism from Republicans. News media naturally focus on such controversies but the conviction integrity unit has not received the praise it deserves.

This brief summary leaves out many details. Read the full story on my blog, innocentwomeninprison.org.

A Story Suggestion For Journalists

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, there are 101 conviction integrity units (sometimes called conviction review units) across the country but only about half of them actually have freed people from prison and cleared their records. If your local prosecutor has such a unit, is it productive? If there is no such unit, is the prosecutor considering establishing one?